Make your own Assembler simulator in JavaScript (Part 1)

I always enjoy developing in assembler because it is fairly simple to learn, each command does exactly one thing and thus gives a good insight on how a computer operates. Nevertheless, it is possible to make sophisticated software and there is the problem of developing in assembler. It can get complicated very quickly.

The goal of this blog post is to create a simple simulator which is able to assemble your code into CPU instructions and run them on a virtual computer. This simulator is perfect to learn assembler because it is not necessary to deal with x86 or operation system specific details. In fact, I got already feedback from teachers that they use this simulator to teach their students assembler. If I got you curious then you can check out the source code (MIT) on my Github page. An online demo is available here: https://schweigi.github.io/assembler-simulator/.

A note before we start: All sample code in this tutorial is simplified. Each code block contains a link to the complete code.

The Simulator

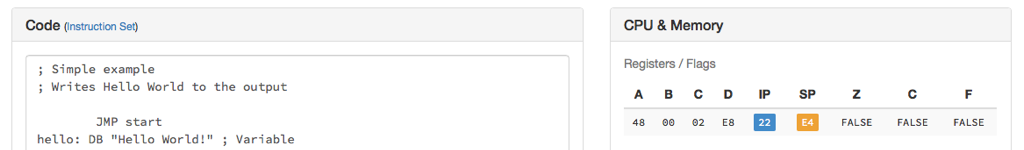

The simulator is written in JavaScript with Angular and runs on every device with a web browser. It has a lot of simplifications and constraints, but it is the basic structure of every emulator. The virtual computer consists of the following components:

- Memory (256 bytes). The memory contains our program code and can be used by the program to store data.

- 8-bit CPU. The CPU reads instructions from the memory and executes them.

- Console output. The console output uses memory mapping and maps a specific portion of the memory to the console. Thus writing to the console output is as simple as writing into a specific memory location.

Overall not a very powerful machine but more than enough to run a program.

Now. Let's write some code.

The CPU

The heart of the simulator is the CPU. The CPU consists of 4 general purpose registers (GP) and their job is to hold the values needed to execute an instruction/command. How does the CPU know what to execute? For this, we use an instruction pointer (IP). Technically the IP is just another register with some additional functionality. The IP holds the location of the next instruction in the memory and on each CPU cycle the CPU grabs this instruction and executes it.

While this little functionality is enough to execute some programs it is not enough to execute any kind of programs. For example in order to provide IF-then-else functionality the CPU needs to make a decision based on the result of the previously executed instruction. Those results are stored in 1-bit flags. Our CPU will contain three different flags:

- Zero (Z). The most important one. If the result of an instruction is 0 then this flag contains

1otherwise0. - Carry (C). If an instruction generated a carry over then this flag is set to

1. - Fault. In case an instruction leads to a faulty state of the CPU (e.g. division by 0) then this flag is set to

1. In a case of fault, the CPU is halted and no more instruction are executed.

Last but not least we upgrade our CPU with a stack pointer register. The stack pointer (SP) as the name already gives away points to the current stack position in the memory. It can be incremented and decremented by the program to store data and implement functions.

First we define all the registers, pointers, and flags. Then a reset function which is used to initialize the CPU and make a reset in case we would like to restart the computer.

var gpr, ip, sp, zero, carry, fault;

function reset() {

gpr = [0, 0, 0, 0];

self.maxSP;

ip = 0;

zero = false;

carry = false;

fault = false;

}

On each CPU cycle, the next step is executed. Each step does only execute one single instruction. Possible instructions are Addition, Subtraction, Jump (Branching), Multiplication, Division and so on.

It is important to know that there is a specific instruction for each operation. Thus adding two registers together or adding a constant numeric value to a register are two different instructions. This means that there will be a lot of instructions even for our simple simulator. In a case of addition, we will implement 4 possible instructions.

An instruction contains the opcode (operation code/command) and its operands (parameters). The first operand is usually the target and the second one is the source. If an instruction has only one operand then this operand is target and source at once.

As an example the addition instructions are defined as follow:

[Opcode] [Operand1] [Operand2]

0x0a reg, reg

0x0b reg, [address]

0x0c reg, address

0x0d reg, constantFor easier usage, we will define those opcode numbers in a list so that we can access them by name. E.g. 0x0a is defined as ADD_REG_TO_REG. The complete list can be found in the file opcodes.js of the simulator project.

A documentation of all support instructions is available in the simulator documentation.

The code is actually straight forward. It reads the next instruction from memory with the help of the IP. Then the operands of the instruction are retrieved from memory and finally the instruction is executed. All CPU flags are set after the execution result has been calculated. After the instruction is executed the IP is increased and the CPU cycle is finished.

function step() {

if (fault) {

throw "FAULT. Reset to CPU continue.";

}

var instr = memory.load(ip);

switch(instr) {

case opcodes.ADD_REG_TO_REG:

// Read operand 1: Target register

var regTo = memory.load(ip+1);

// Read operand 2: Source register

var regFrom = memory.load(ip+2);

// Execute instruction. Add values of both registers

var value = processResult(readRegister(regTo) + readRegister(regFrom));

// Write the new value back to the target register

writeRegister(regTo, value);

// Increase instruction pointer

ip += ip+3;

break;

case opcodes.ADD_REGADDRESS_TO_REG:

...

case opcodes.ADD_ADDRESS_TO_REG:

...

case opcodes.ADD_NUMBER_TO_REG:

...

case ...

...

default:

throw "Invalid opcode: " + instr;

}

}

function processResult(value) {

zero = false;

carry = false;

if (value >= 256) {

carry = true;

value % 256;

} else if (value === 0) {

zero = true;

} else if (value < 0) {

carry = true;

value = 255 - (-value) % 256;

}

return value;

};

You will have noticed that the instruction pointer was increased by +3 instead of +1. This is because an instruction takes up 1 byte for the opcode and for each operand another byte of memory. The add instruction requires therefore 3 bytes of memory. Yes, there is a lot of memory optimization potential and I leave this as an exercise to you.

The complete code can be found here: cpu.js. It also contains additional checks to make sure all registers and memory addresses of the instruction are valid.

In the next post we will implement the memory, console output, UI and on how to assemble code into instructions.